20th February 2010 | Draft

Magic Carpets as Psychoactive System Diagrams

***

-- / --

Annex to Interweaving Thematic Threads and Learning Pathways: Noonautics, Magic carpets and Wizdomes (2009)

Introduction

Magic carpets as vehicles for noosphere travel

Cultivating 'hearts and minds'

Strategic system diagrams as carpets of primitive design

Patterns of symmetry

Design challenge of imbuing quality and meaning

Psychosocial engagement in design

Beauty-Complexity-Integrity in design

Military uptake for 'knowledge sharing' and 'insight management'

Memorability over time: transcending the adaptive cycle

Knotting threads of identity

Correspondence, connectivity and resonance

Mystical significance of carpets

'Prayer mat' as 'System diagram'?

Levitating 'recursively' into higher dimensionality?

Quest for mnemonic catalysts

References

Introduction

This exploration contrasts conventional system diagrams with what might be associated, in knowledge management and cognitive terms, with 'magic carpets' and the challenge of weaving 'magic' into a carpet in order to move 'hearts and minds' -- in ways strategic plans seem unable to do.

Magic carpets as vehicles for noosphere travel

The traditional metaphor of a magic carpet, especially the kinds of transportation it might facilitate, continues to be of significance in the emerging global knowledge society. It has figured in a widely popular song held to be representative of an era (Magic Carpet Ride, 1968). It has been used to frame the possibility of a sophisticated interface for navigating the web (Shumin Zhai, et al. In Search of the 'Magic Carpet': design and experimentation of a bimanual 3D navigation interface, Journal of Visual Languages and Computing, 1999).

A magic carpet is at the core of a founding legend of Islam through which Muhammed was inspired by Allah (as noted below). It is also significant in Judaism in the legend of Solomon's carpet -- subsequently exploited by Israel in Operation Magic Carpet (1949-50) as the name of a program to transport Jews from Yemen. Operation Magic Carpet (1945-46) was also the name of a program to repatriate American military personnel. The UK Royal Navy undertook a Magic Carpet exercise over Oman in 2005. In a NATO report on Critical Asymmetries in Close Air Support (2009) in Afghanistan, a Small Military Aircraft (SMA) was described as a prototype Magic Carpet. For that arena, a NATO report on Dragoons for Close Air Support called for 'immediate and intuitive acceptance of magic carpets'

Various experiences have been compared to a magic carpet or a flying carpet, included use of psychoactive drugs. It has been argued that myth is like a magic carpet (Robert A. Segal, Jung's very twentieth-century view of myth, Journal of Analytical Psychology, 2003). It is used as the name of an international educational project: The Magic Flying Carpet Project. The metaphor remains relatively active. It figures notably in a variety of computer games.

A valuable indication of how the metaphor might prove relevant with respect to knowledge management is provided by Charles Savage as president of Knowledge Era Enterprises International (Weaving the Magic Carpet, Inside Knowledge, 11, 7, 3 Jun 2008). He argues with respect to the current challenge of social change:

But to explain the dynamics of the current change, he reaches back for lessons learnt in the earlier transition and proposes threads of KM and more woven together to make a magic carpet on which to fly into the (ac)knowledging economy.... For clarity, that's what I call it, the 'acknowledging economy'. Typically we are beginning to speak of the transition to the knowledge economy as if it were a fashion change in our work wardrobe. My guess is it can only happen as we learn to actively acknowledge and value one another in new ways. Second, an economy is not just a model that is imposed. Instead it is a living process and ought therefore to be seen as a living verb rather than a weighty noun, hence the construct '(ac)knowledging economy'.... Gradually we are recognising a jazz jam session is coming to represent the new paradigm of corporate meetings, as each player deeply listens to one another and taps his or her tacit knowledge to better understand the dynamics of the market....

Weaving the knowledge threads: If the 'gear' were to represent the industrial era, might the energy releasing and co-creative 'flow' represent the next era, the (ac)knowledging economy? Those who have experienced a jazz jam session know what it is to be in the flow or in the groove.... What if we were to weave these threads together... as in a jazz jam session, into a magic carpet that would fly us to the (ac)knowledging economy? ... But weaving a carpet that might fly into the next economic era, that's a challenge of another order, is it not?....Breaking out of paradigm prison: If we can weave together our magic carpet within a co-creative and collaborative community, we may already find we are flying in the right direction.

As expressed, this argument fails however to take account of the psychoactive engagement that is potentially associated with the 'magic' that must necessarily be woven into the carpet. Savage is cited with respect to the Flying Carpet initiative of Community Intelligence Labs, founded by George Pór.

|

| Depiction of a magic carpet by Viktor Vasnetsov (1880)

to illustrate the folktale of Ivan and the Firebird, returning from the magical realm of Kashchei the Immortal with a golden birdcage |

Cultivating 'hearts and minds'

The cultural context in which significance has been attributed to a 'magic carpet' is noted by John Thackeray (The History of the Oriental Carpet):

The children of the orient are taught the historical background of the carpets, the techniques of knotting and weaving, how to blend color and what to portray on the rug depending on the theme they are wishing to design and also, importantly, the symbolism in the carpet. Being taught how to weave these amazing artworks teaches the children patience and culture, and is also extremely valuable in continuing the legacy of Persian carpets and the consistent level of quality.

In discussing the historical context of their design. Oriental Rugs History notes that:

Oriental rugs are written pages. In their maze of design is a symbol language, the key of which, in its ceaseless transmission through the centuries, has unhappily been all but lost. The variation of its forms, in the different classes of fabrics, may be looked upon as dialectic; and it must be believed, so far as the very ancient figures are concerned, that none of the dialects is understood by the weaver who employs it at the present day.

Sir George Birdwood (The Industrial Arts of India, 1880) is cited there to the effect that:

Whatever their type of ornamentation may be, a deep and complicate symbolism, originating in Babylonia and possibly India, pervades every denomination of Oriental rugs. Thus the rug itself prefigures space and eternity, and the general pattern or filling, as it is technically termed, the fleeting, finite universe of animated beauty. Every color used has its significance, and the design, whether mythological or natural, human, bestial or floral, has its hidden meaning. Even the representations of men hunting wild beasts have their special indications. So have the natural flowers of Persia their symbolism, wherever they are introduced, generally following that of their colors. The very irregularities, either in drawing or coloring, to be observed in almost every Oriental rug, and invariably in Turkoman rugs, are seldom accidental, the usual deliberate intention being to avert the evil eye and insure good luck.

Strategic system diagrams as carpets of primitive design

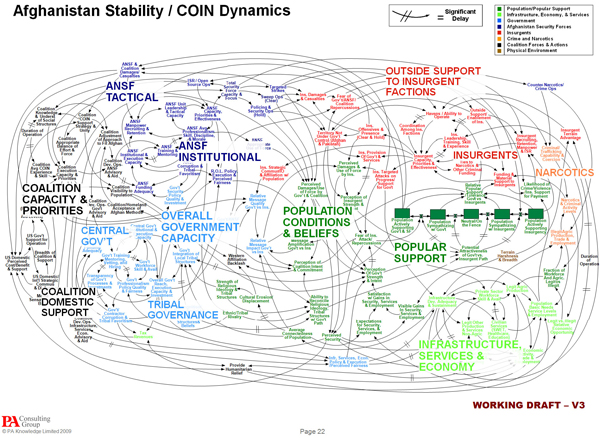

In exploring the metaphor of a magic carpet for cognitive transportation, a contrast may be made with the articulation of the strategic map for the (renewed) campaign for 'hearts and minds' in Afghanistan by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. This map of military counterinsurgency operation dynamics (COIN dynamics) is explicitly designed to enable 'movement' with respect to that arena and in response to the stuck condition to which past NATO strategy has brought it. It map been compared to the Flying Spaghetti Monster. (Dion Nissenbaum, Graphic Shows Complexity Of US Counterinsurgency In Afghanistan, The Huffington Post, 22 December 2009; Dion Nissenbaum, The great Afghan spaghetti monster, Checkpoint Kabul, 20 December 2009).

| Strategic map of counter-insurgency operations in Afghanistan (as reproduced in The Huffington Post, 22 December 2009) |

|

| 'Meaningful' -- but 'Ugly'? |

Such maps are variously associated with a data flow diagram, system context diagram, network diagram, semantic network, mind map, concept map, decision map, or argument map, for which many software applications exist as previously described (Complementary Knowledge Analysis / Mapping Process, 2006).

But the viability of the COIN map (above) as a vehicle might be caricatured as a 'magic carpet' on which NATO chiefs are optimistically seated without any enabling motive power with respect to movement in cognitive space -- the noosphere, domain of 'hearts and minds'. Airborne forces and drones may indeed be used in any number -- wedding parties may be readily transformed into funerals -- but the forces used are in effect surrogates and exercises in cognitive displacement. Like little boys, the NATO chiefs can chant a mantra of 'Vroom, Vroom' (if not 'Surge, Surge'), but this does not translate into useful movement of their strategic carpet. With respect to moving 'hearts and minds', it will not get off the ground and 'fly' as they would wish.

Patterns of symmetry

The war in Afghanistan has proven to be the greatest military failure in history, given the unprecedented resources deployed for an extended period of time against an enemy framed as 'primitive'. The war has been graced in strategic terms by the label asymmetric warfare (of which the Biblical archetype is the tale of David and Goliath). It is therefore of great interest to recognize the understanding of symmetry associated with carpet weaving by the culture which has so successfully resisted that onslaught.

A report by Carol Bier (Choices and Constraints: pattern formation in oriental carpets, 1999) is described as having the following scope, for example:

This report delves into the 'dynamic relationships of choices and constraints' by which both symmetry and symmetry-breaking are used in weaving to turn repetitive patterns into impressive works of art. On the premise that 'patterns in nature result from dynamic relationships of forces and constraints,' this treatise based on studies of Oriental carpets, proposes that 'patterns in art result from dynamic relationships of choices and constraints.' If art is the product of creativity and skill, 'creativity is constrained by cognitive processes and skill by the limits of technology.' Other terms: longitudinal, weft, knots, rug-weaving, rectilinearity, permutation, warp, orthogonal, algorithm, topology, fractal, innumeracy, combinatorics, juxtaposition, unitary, systemic.

A later paper by Carol Bier (Mathematical aspects of oriental carpets, 2001) is summarized in the following terms:

This report describes the mathematical aspects of Oriental carpets, including those of pattern formation, which may often be glossed over unlike the principles of pattern-making based on symmetrical repetition. The study notes a set of characteristics that tend to be mathematical, including features such as structure, form, design, formal composition, topology, and pattern. In one comparative analysis of two rugs woven in western Turkey, the report discusses mathematical principles that 'underlie, limit, and structure the possibilities of pattern-making and creativity as expressed by weavers.' Details involved in the patterns of Oriental carpets are woven together, as the principles of symmetry, symmetry-breaking, repetition, geometric relationships, spatial dimension, and much more are explored.

In addition to the use of 'carpet' as a metaphor in mathematics (Sierpinski Carpet, Haferman Carpet), mathematicians are fascinated by the range of patterns in such carpets (Symmetry and Pattern: the art of oriental carpets). One section of the website notes, for example:

Patterns in Oriental carpets are never quite what you expect -- a surprise here, a flourish there, a change of color, the flip or rotation of a design where you might not predict it. The more you look, the more variations you will find. How can we explain this phenomenon? Is it the result of human choice, or human error? The study of symmetry offers one approach to analyzing patterns in Oriental carpets. Through symmetry analysis we may identify areas of pattern that exhibit expected repetitions, and areas that vary from that expectation.

This is consistent with their fascination with the geometric patterns embodied in traditional Islamic architecture. For example, Marcus du Sautoy (Finding Moonshine: a mathematician's journey through symmetry, 2008) provides an account of the mathematically significant variety of 17 plane symmetry groups to be found in the architecture of the Alhambra. He introduces the relevant chapter (The Palace of Symmetry) with the following quote from Leon Battista Alberti (The Ten Books of Architecture, 1452):

And I would have the Composition of the Line of the Pavement full of Musical and geometrical Proportions; to the Intent that which-soever Way we turn our Eyes, we may be sure to find Employment for our Minds.

Keith Critchlow offers a design perspective on such patterns (Islamic Patterns: an analytical and cosmological approach, 1976).

It is not difficult to recognize the strategic significance to minds influenced by such understanding, as with the argument for recognition of the strategic significance of the connectivity offered by poetry in engaging with cultures in the 'carpet region' (Poetic Engagement with Afghanistan, Caucasus and Iran: an unexplored strategic opportunity? 2009; Strategic Jousting through Poetic Wrestling: aesthetic reframing of the clash of civilizations, 2009). Is it even remotely possible that carpet design might hold coded systemic insights into more appropriate strategy in the region -- if only for the 'in-surgents'?

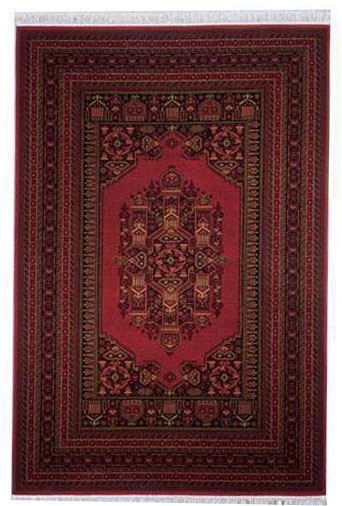

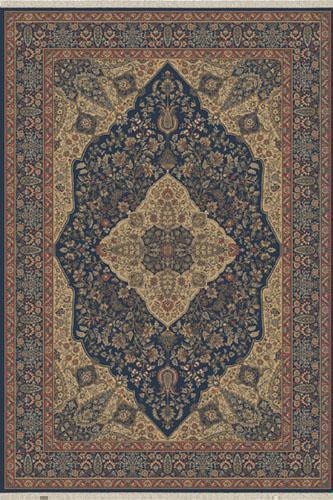

| Traditional rugs from Turkey, Persia and Afghanistan (see other images at Woodworkers Auction) |

||

|

|

|

| 'Beautiful' -- but 'Meaningless'? | ||

Design challenge of imbuing quality and meaning

Of particular relevance to the argument here is the attention given to carpet design by architect Christopher Alexander in the seventh in a series of books on design, order and pattern (Notes on the Synthesis of Form, 1964; A Pattern Language, 1977; A Foreshadowing of 21st Century Art: the color and geometry of very early Turkish carpets, 1993). Surprisingly his work has had considerable influence on computer programming language design -- the essence of system comprehension.

In the approaches he has developed, Alexander (and those commenting on those processes) make notable use of weaving as a metaphor: Design is interwoven with synthesis in a mainly bottom-up fashion (Christopher Alexander: An Introduction for Object-Oriented Designers, 1993); The new system is based on a process in which design and construction are unified and interwoven continuously (Comment on the pattern language design approach, 2000); These properties of good design are not independent, discrete characteristics. Rather, these properties are interwoven (The Nature of Order, 2003); Interwoven meanings of the word 'feeling' in a living process (The Nature of Order, 2003). Paul F Downton (2009) uses the theme Weavers of Theory in that connection.

His stated central concern is 'geometric adaptation'. He argues:

'Powerful' carpets: In his insightful review of Alexander's study of carpets, for the Environmental and Architectural Phenomenology Newsletter, David Seamon notes Alexander's concern with why the earlier carpets are so 'powerful', remarking that that this power and wholeness is not a matter of personal preference or taste but, rather: a definite, tangible, and objective quality which really does exist to a greater or lesser degree in any given carpet (p. 26). This relates to the fundamental concern in his earlier work (The Timeless Way of Building, 1979):In many real world systems, both in nature, and in those places where human beings form communities with animals, plants, and other human beings, the central observable is a close-knit adaptation of the system elements, usually arising over time, and most often expressed in the intricate geometry of the system. This close-knit geometric adaptation has not yet been a major focus of scientific study, because it eludes simple algorithmic formulations (2003)

There is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.

In the case of carpets, the heart of this quality, as reported by Seamon, lies in their color and, especially, their geometry:

It is the geometry, the interlock of the shapes, the very striking boldness of the geometric shapes, and the way that figure and ground reverse, and the many, many levels of scale, which bring the softly shining color to fruition' (ibid.).

Alexander is especially interested in what makes a design 'powerful'. He develops a language and a way of looking at the carpets, anticipated in an earlier document (Christopher Alexander, A New Way of Looking, HALI: The International Magazine of Antique Carpet and Textile Art. 56, 1991, pp. 115-125). He hopes that this will offer common agreement as to which carpets are more and less powerful in embodying wholeness and order:

To study wholeness, we must have an empirical way of distinguishing it from preference (p. 27).

Carpet geometry: 'centres': For Seamon, Alexander thereby develops an implicit phenomenology of carpet geometry, drawing on personal discoveries made after extensive study of the 74 carpets on which he reports. Ultimately, however, he recognizes that a clearer understanding of carpet geometry requires practice, and the first part of Alexander's book is a guide to looking and seeing. The crux of Alexander's argument, according to Seamon, is what he calls 'centers' -- smaller or larger gatherings of pattern that are seen as units or wholes. Centers are local configurations that appear whole in the design (p. 32) or, again, a psychological entity which is perceived as a whole, and which creates the feeling of a center in the visual field.

A review of Alexander's work by Nikos A. Salingaros (Some Notes on Chrisopher Alexander, 1997) focuses specifically on his Influence on Oriental Carpet Studies and the controversy it has aroused. A particular concern is the assumption that any mathematical theory can successfully measure the degree of 'life' in a carpet, although he demonstrates that that that is precisely what happens, and the results agree to a remarkable extent with deepest intuitions. Alexander's study of carpets outlines his 'Fifteen Fundamental Properties' (of life) and the 'Field of Centers' which are at the core of his subsequent multi-volume study (The Nature of Order, 2003-4). Salingaros himself explored the application of these rules with illustrations (The Life of a Carpet: an application of the Alexander Rules, KunstPedia, 20 March 2008). Alexander describes these transformations as the 'glues' of wholeness.

Carpet geometry: transformational properties: Described as 15 transformations, Alexander identifies them elsewhere, with brief explanation (Harmony-Seeking Computations: a science of non-classical dynamics based on the progressive evolution of the larger whole. International Journal for Unconventional Computing, 5, 2009), as follows:

| Levels of Scale | Good Shape | Roughness |

| Strong Centers | Local Symmetries | Echoes |

| Thick Boundaries | Deep Interlock | The Void |

| Alternating Repetition | Contrast | Simplicity |

| Positive Space | Gradient | Not-Separateness |

With respect to these properties/transformations he states:

The primary entities of which the wholeness structure is built are centers, centers that become activated in the space as a result of the configuration as a whole. Centers typically have different levels of strength or coherence. The coherence of a configuration is caused by relationships among centers. In particular, there are 15 kinds of relationships among centers that increase or intensify the strength of any given center.

[NB: A detailed review of these insights of Christopher Alexander is provided in a follow-up paper: Harmony-Comprehension and Wholeness-Engendering: eliciting psychosocial transformational principles from design (2010)].

Psychosocial engagement in design

Given the highlighting of 'centres' by Alexander, there is a strong case for exploring their significance in a psychosocial context. They recall both the the topoi that have been a focus of mnemotechnics and the topos vital to a sense of place -- hence topography and topics. Curiously considerable attention has been given to 'centre of gravity' in market research. Given the sense of aesthetic configuration explored by Alexander in carpets, and more generally in design, the question is how the configuration of centres catalyzes or entrains psychoactive engagement, as previously discussed (Topology of Valuing: psychodynamics of collective engagement with polyhedral value configurations, 2008).

Design in the material world: In developing the relevance of Alexander's insights to the weaving of magic carpets, it is useful to recognize his commitment as an architect to design of material 'objects' and imbuing those 'objects' with meaning. In his exploration of this lifelong commitment he has given attention to the relevance of insights from mathematics and the complexity sciences. His study of the nature of order integrates the challenge of cognition and the 'subjective' relation of the observer to those objects. This might be described in terms of the cognitive entanglement discussed previously (Cognitive entanglement, 2010). However he clarifies his understanding of subjective as follows:

...union of system behavior with the subjective experience of the observer is fundamental to what I have to say of wholeness as something not merely present in an objective material system, but also present in the judgment, feeling, and experience of the observer. In short, cognitive/subjective experience is affirmed by objective reality. (New Concepts in Complexity Theory, 2003)

Seemingly missing from Alexander's approach is the implication of that remarkable synthesis for the design of collective strategy -- epitomized by the current situation in the region cultivating the culture within which many valuable carpets have originated. His understandable bias towards the built and natural environment assumes that its inhabitants can be appropriately conditioned by (re-designing) context -- a characteristic bias of those with an architectural bent. Quality for the collective is thereby elicited through the tangible constructed environment and its appropriate design. He seems to be completely reluctant to explore the relevance of his insights to the psychosocial realm, as though this did not have its own challenges of design. The unfortunate assumption is that it is through design of the material environment that the psychosocial environment can be appropriately 'conditioned' to experience quality. To an unfortunate degree Alexander might be said to be interested in the 'packaging' of humans rather than the content so beautifully 'packaged'. This might be caricatured as a design focus on 'clothing' in the sense of the adage dating back to classical Greece: clothes maketh the man.

Design of the psychosocial world: The question is the relevance of such design insights, notably his 'pattern language', for the quality of the intangible environment -- the realm of structural violence, cultural violence and possibly spiritual violence. Why are these insights, as he elaborates them, seemingly irrelevant to the design challenges of the Middle East, even though they are focused on 'geometric adaptation'? (And When the Bombing Stops? Territorial conflict as a challenge to mathematicians, 2000). This is especially curious given the origin of the powerful designs on which he focuses -- and of the insights from which they may well derive their power.

It was for this reason that an experiment was undertaken to adapt Alexanders classic set of patterns to psychosocial realms (5-fold Pattern Language, 1984). Such patterns are necessarily basic to any concern with the strategy of sustainability (Psychology of Sustainability: embodying cyclic environmental processes, 2002).

His explicit integration of a form of subjectivity, whilst much to be appreciated, seems to avoid the active role of cognition -- as explored from perspectives such as enactivism, through which reality is to a degree engendered (En-minding the Extended Body: Enactive engagement in conceptual shapeshifting and deep ecology, 2003; Walking Elven Pathways: enactivating the pattern that connects, 2006; Intercourse with Globality through Enacting a Klein bottle, 2009; Existential Embodiment of Externalities: radical cognitive engagement with environmental categories and disciplines, 2009).

Ironically, if they are as fundamental as Alexander claims, there is every probability that the 'geometry' and descriptors of his 15 transformations/properties correspond to cognitive processes/conditions of the kind recognized in many meditative practices, as explored previously (Navigating Alternative Conceptual Realities: clues to the dynamics of enacting new paradigms through movement, 2002), and especially with regard to any qualitative 'ascent' to 'beauty', as reviewed in the annexes of that paper:

- Metaphoric Entrapment

- Clues to Movement and Attitude Control

- Combining Clues to Movement and Attitude Control

- Clues to "Ascent" and "Escape"

- Combining Clues to "Ascent" and "Escape"

Curiously, it is with q-analysis that mathematician Ron Atkin (Multidimensional Man; can man live in 3-dimensional space?, 1981; Combinatorial Connectivities in Social Systems, 1977) has perhaps best integrated comprehension and communication of increasing complexity into the geometric terms favoured by Alexander, offering a realistic sense of the (constraining) 'feel' of the geometry -- but without any reference to its beauty.

Beauty-Complexity-Integrity in design

Despite his reluctance to consider design in the intangible psychosocial realm, where his insights are so desperately needed, Alexander explicitly addresses one of the most intangible experiences. He argues with respect to movement in that configuration space (or fitness landscape) of design that:

And what it amounts to in informal language, is that the transformations represent a coded and precise way that aesthetics -- the impulse towards beauty -- plays a decisive role in the co-adaptation of complex systems.... the successful movement around configuration space... cannot succeed unless it uses this technique (2003).

For him the key questions are:

- Can we find any structural features which tend to be present in the examples which have more life, and tend to be missing in the ones which have less life?

- In other words, can we find any recurrent geometrical structural features whose presence in things correlates with their degree of life?

In Alexander's own overview of the four volumes on the Nature of Order (New Concepts in Complexity Theory -- arising from studies in the field of architecture, 2003), he addresses the scientific problems they raise under the following headings which frame a valuable new way of thinking -- potentially conducive to eliciting 'magic':

- Wholeness and value as a necessary part of any complex system

- An intuitive model of wholeness as a recursive structure

- Aa mathematical model of wholeness identifying wholeness as a well-defined recursive structure of a new type

- Objective measures of coherence in complex systems, and the unavoidable relationship between structure, fact, and beauty

- Fifteen geometric properties as necessary and inevitable geometric features of reality in any complex system

- A meeting point between cognition and objective reality?

- A new, experimental way of determining degree of coherence, degree of life, and relative value

- The science of complexity must make room for subjectivity, not in the sense of idiosyncracy of judgment, but as a connection to the human being.

- Local symmetries and sub-symmetries

- Deep adaptation as a central concept in complex system theory and in architecture

- The absolute necessity for successful adaptation to be achieved by generative means

- The effect of structure-preserving transformations on the world and their role in the unfolding of wholeness

- The hugeness of configuration space and the way the trajectory of a complex system can reach adaptation

- More on adaptational success as a special kind of trajectory through configuration space

- Wholeness-preserving transformations are the primary ways the trajectory of a complex system is able to reach successful adaptation

- A summary: the role of beauty in the science of complexity

As the above headings indicate, Alexander has woven together a range of essential themes -- each potentially a threaded discussion in its own right -- to constitute a form of magic carpet. In integrating the themes indicated below into a 'complex', notably with respect to carpet design, the pattern raises questions with regard to the degree of 'magic' imbued in system diagrams, notably with respect to collective strategy and its ability to engage 'hearts and minds'.

| Comparative "diagrams" enabling insight | ||||

| Themes | Carpet design | System diagrams | Collective strategy | 'Hearts and Minds' |

| Beauty | ||||

| Wholeness | ||||

| Complexity | ||||

| Power | ||||

| Life | ||||

| Endurance | ||||

| Attraction | ||||

| Engagement | ||||

| Comprehension | ||||

| Knots | ||||

| Possession | ||||

Of interest with respect to empowering any magic carpet is the correlation between the qualities -- if not their progressive conflation -- as any one of them 'increases'. Increasing wholeness is associated with increase in the beauty of the patterns of symmetry in increasing complexity -- and the attractive power of its psychoactive engagement, experienced as increasing aliveness. It effectively becomes 'enspirited'. Values themselves may be profoundly attractive (Human Values as Strange Attractors, 1993).

Military uptake for 'knowledge sharing' and 'insight management'

Given the importance of Alexander's past understanding to computer programming and systems design, such insights clearly merit careful consideration with regard to the psychoactive nature of the engagement with order. However the question is the relevance of those insights to the appropriate design of effective strategy -- engaging 'hearts and minds' -- such as to achieve 'mobilization' and 'traction' with respect to current reality. Hence the merit of exploring understandings of a magic carpet as a vehicle -- as implied by Alexander's insights.

Psychosocial application: Most curiously however, there are few references in the literature to any attempt to apply these insights to the psychosocial realm -- through which such a cognitive vehicle should travel. One exception is a comment by Gillgren Communication Services with respect to Patterns of Engagement as the language of participation for building dynamic organizations, communities and enterprises. Alexander's 15 transformations are recognized there as:

... vital to genuinely understanding and applying any pattern language, particularly as a means for engaging in the extension and healing of complex social systems and organizations. And it could provide a practical language (in the literal sense) for introducing complexity theory into grassroot community transformation.

Military uptake: It is therefore profoundly ironical with respect to the argument here concerning the appropriate weaving of threads of meaning (and the criticism of the COIN system diagram above) that seemingly the most remarkably elaborate articulation of Alexander's transformations to enabling knowledge connectivity has emanated from the military. In a paper for 12th International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, on behalf of the United States Military Academy, his insights are applied to the design of knowledge sharing in a command and control environment by Major David P. Harvie (Knowledge Sharing Mechanism: enabling C2 to adapt to changing environments, 2007).

As with Alexander's earlier work on pattern language, the relevance to the challenge of systems design and control is explicitly recognized, as the paper's abstract indicates:

The environments of software engineering and command and control (C2) are very similar because they are both instances of complex problem solving. The common nemesis to successfully developing solutions in these environments is change. The challenge of any complex problem solving process is the balance of adapting to multiple changes while keeping focused on the overall desired solution. The Knowledge Sharing Mechanism (KSM) is proposed as framework to achieve this balance. The KSM is an iterative method for understanding a complex problem, developing a framework for solving that problem, developing partial solutions for the problem, and then reassessing those partial solutions and overall framework until the complete solution has been fully developed. The KSM is based on the integration of Christopher Alexander's unfolding and differentiation processes with the image theory of C2. In image theory, there are two perspectives in developing a solution: topsight and insight. These two perspectives must be balanced in order to achieve success. Alexander's unfolding process is the basis for understanding, as an observer, the complex interactions in both software engineering and C2. The KSM uses Alexander's differentiation process, as an actor, achieving the correct balance of topsight and insight.

Constraints of the military mindset: It is however extraordinary that the military should use Alexander's approach, driven as it is by the manner in which beauty is elicited. Will it be the military that develops 'magic carpet technology' complete with its 'command and control (C2)' ? To the extent that 'knowledge sharing' requires a higher degree of organization than some of the simpler approaches to organizing threaded discourse, it would appear that the military is exploring possibilities of a higher order than those envisaged with respect to the Semantic Web.

This is improbable because, rather than 'C2', heart-and-mind enablement calls for development of consciousness engaged with higher dimensionality. A 'C3' approach? Whilst command and control may indeed focus on connectivity to achieve coherence, notably via invasive surveillance, essential to the consciousness required for 'heart-and-mind' capacity is conscience -- perhaps suggesting the need for a 'C4' approach (Towards Conscientific Research and Development, 2002). Such distinctions recall recent debates regarding the current adequacy of accounting -- namely the 'command-and-control' methods for financial systems -- beyond 'double-entry bookkeeping', to 'triple bottom line' and further (Spherical Accounting: using geometry to embody developmental integrity, 2004). Harvie's paper is appropriately accompanied by an extensive bullet-pointed presentation of Alexander's relevant points. The only one of its kind?

There is a curious preference of the military for articulation of strategy through 'bullet points' -- appropriately backed by rockets and missiles as an operational mode of communication in the effort to engage 'hearts and minds'. This recalls the limitations of the Level 2 and Level 3 modalities of the main paper with regard to the possibilities of threaded discourse (Enhancing Sustainable Development Strategies through Avoidance of Military Metaphors, 1998). And yet Harvie offers a valuable reflection into the application of Alexander's work to knowledge sharing, highlighting the distinction and reconciliation between:

- topsight: in order to design an overall architecture for solving a problem, despite the loss of detail

- insight: into the subsets of the problem that assist in its solution, despite the narrow field of view it offers

Harvie stresses the vital role of imagery (through an 'image theory') and the power of metaphor to guide any overall project. He highlights the need to view the situation from the perspective of the enemy -- effectively the perspective of 'the other'. As noted, he uses Alexander's approach to achieve the correct balance of topsight and insight.

Outward-surging vs Inward-surging?: Ironically the current military focus on 'counter-insurgency' is precisely indicative of the cognitive trap of the strategy absorbing unprecedented global resources. The military is indeed its 'own metaphor' in Gregory Bateson's terms. Whilst the focus is on material 'surges' and their enhancement, these are designed specifically to counter 'in-surges', to be specifically understood as any 'surge' into the dimensions of greater self-awareness in which any 'hearts-and-minds' response might be cultivated. In this sense the military is 'shooting itself in the foot'. 'Counter-insurgency' says it all. Ironically an 'in-surgent' is an expression of 'heart-and-mind' which COIN is endeavouring to 'terminate with prejudice'. The term is indicative of the higher dimensional cognition with which they are identified and from which they are sacrificing themselves -- a strategic highground beyond the comprehension of an 'out-surgent' preoccupation.

Memorability over time: transcending the adaptive cycle

Of particular interest, in a period increasingly characterized by a 'crisis of crises', is the sense in which a 'thing' imbued with quality endures over time. As Alexander implies such endurance is essentially a sustainable pattern within any collectivity -- within its collective cultural memory -- offering access in the moment to macrohistory (Engaging Macrohistory through the Present Moment, 2004). This might be understood to be the prime requirement for collective navigation of the adaptive cycle, calling for a new way of looking, as separately discussed (Dynamics of polyocular and multifacetted cognitive framing: navigating the adaptive cycle, 2010).

Ironically again, the argument of Harvie (for the relevance of Alexander's thinking from a military perspective), specifically addresses the challenge of adapting the process of 'knowledge sharing' to changing environments. Is the military indeed taking the lead in responding to the challenges of the adaptive cycle?

The capacity for any appropriate strategy to endure -- to be sustainable over time -- implies a need to embody that cycle, as discussed elsewhere (Psychology of Sustainability: embodying cyclic environmental processes, 2002; Emergence of Cyclical Psycho-social Identity: sustainability as 'psyclically' defined, 2007). In terms of the complexity 're-cognized' by Alexander, any such strategy is necessarily exemplified by its attractive elegance -- mathematically understood but rendered into other forms of presentation, notably constituting a magic carpet. The question is how such a collective vehicle is to be woven from the many threads of relevant discourse -- visibly in disarray (as recently exemplified by the climate change movement).

Navigation of time in this way justifies the 're-cognition' of such a cognitive vehicle as a 'timeship' (Embodying a Timeship vs. Empowering a Spaceship, 2003). As mentioned above, the challenge of navigating the crisis of crises is framed in terms of navigating the adaptive cycle and the 'cognitive catastrophes' associated with the requisite learning. Arguably as an exercise in noonautics, the kinetic intelligence required for the necessary strategic nimbleness might well be framed in terms of elegance, symmetry and time-binding capacity.

Navigating the adaptive cycle -- necessarily a thing of beauty in the light of the argument above -- might even be framed in the words of the poet John Keats as A Thing of Beauty is a Joy Forever (1818). The necessary ability of any such cyclic pattern to sustain and 're-create' attention and curiosity is well-highlighted by the poet T. S. Eliot:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

(Little Gidding, 1942)

The ability of humanity to navigate the adaptive cycle through the crises to come may well call for a shift in cognitive centre of gravity into circular time (with its associated logic) as complementary to linear time (Woorama, Linear vs Circular Logic: conflict between indigenous and non-indigenous logic systems, 11 June 2006). The dimensional highground to which a magic carpet offers access may enable recognition of time as in some way intimately associated with the challenge of 'hearts and minds' (The Isdom of the Wisdom Society: embodying time as the heartland of humanity, 2003).

Again it would be ironic if the military were first to recognize the need to reframe the long-recognized strategic advantage of 'high ground' to mean one of higher dimensionality. This is effectively what was achieved by the go-inspired strategy of the Chinese in out-manoeuvering US chess-inspired strategy in the Vietnam war (Scott Boorman, A Protracted Game: a wei-ch'i interpretation of maoist revolutionary strategy, 1969; David Lai, Learning from the Stones: a go approach to mastering China's concept, Shi, 2004)

Knotting threads of identity

Explicit in Alexander's study of carpets is the nature of the knots by which interwoven threads are appropriately connected -- a challenge highlighted by his difficulty in recreating carpets of the powerful quality he has highlighted (Can Modern Weavers Revive the Classical Carpets of the Ottomans? Tea and Carpets, 7 November 2008). Knot have been associated with a long symbolic tradition as well as being of interest to mathematicians (Clifford Ashley, The Ashley Book of Knots, 1944; J. C. Turner and P. van de Griend, The History and Science of Knots, 1996). They continue to be used as a mnemonic device. It is extremely unfortunate that insight into the Inca quipu (talking knots) is restricted to the Vatican.

But knots, and the mathematical theory of knots, have also been recognized as a powerful metaphor by psychoanalysis (R. D. Laing, Knots, 1970). This merits reflection with respect to the connectivity of threaded discourse and the cognitive or social 'fabric' which may be created -- as recognized in the Media Fabrics Experiment of the MIT Media Lab.

The wide range of knots, notably those important to weaving, suggests the merit of reflecting on more complex forms of links between threads -- through which a relationship knot can be 'tied'. The role of the loom in creating distinct knots in weaving also raises the possibility that computer algorithms (and intelligent agents) might be used to create knots between threaded discourses in cyberspace.

Little is said with regard to threaded discourse regarding the manner in which it is a vehicle for identity for those who identify with the theme of a given thread or who use that environment to assert their identity. Threaded discourse might well be described as implying 'threaded identity' -- and the consequent diffidence rearding intercourse and cross-fertilization between threads. This sense of identity is fundamental to resistance to the interweaving of threads in larger patterns in which identity may be felt to be diluted or lost. The nature of the links or 'knots' in any such weave is clearly a matter of great interest -- irrespective of the pathological issues on which psychoanalysis may focus. The possibility that individual or collective identity might be sustained by more complex geometry -- of interwoven discourse -- has been discussed separately (Geometry, Topology and Dynamics of Identity: cognitive implication in fundamental strategic questions and dilemmas, 2009).

Missing from Alexander's discussion is the focus in any collectivity on the exclusive possession of objects of beauty, exemplified by his own unique collection of carpets -- namely the challenge of beauty as property. Beauty notably 'moves' by arousing the desire to possess -- a particular form of cognitive engagement. Possession becomes an expression of identity -- possibly questionable. System diagrams are also typically defined as intellectual property. Whether as carpet or systems diagram (as discussed below), of interest is how either functions cognitively as a frame of reference in the sense highlighted by the special theory of relativity. Relevant to such consideration is the degree to which that theory was conditioned by the background of its originator (Einstein's Implicit Theory of Relativity -- of Cognitive Property? Unexamined influence of patenting procedures, 2007).

Given the crises traversed over the centuries by the semi-nomadic cultures producing the described carpets, it is vital to recognize the degree to which the carpets provide a memorable means of communicating cultural identity and insights over generations. They may be understood as devices for preserving collective memory as variously discussed previously (Minding the Future: thought experiment on presenting new information, 1980; Societal Learning and the Erosion of Collective Memory, 1980). With respect to future crises, they merit consideration as mnemonic devices.

Correspondence, connectivity and resonance

The notion of a relational 'knot' suggests reflection on other forms of 'correlation' between the seemingly disparate topics of distinct threaded discourses.

Of particular significance in this respect are 'correspondences' through which one topic is held to correspond in some way to another (or to be equivalent). The key question is how strong is considered to be the correspondence and by whom. As noted below, major discoveries in the mathematics of symmetry have been associated with correspondences initially deprecated as 'moonshine'.

Preoccupation with correspondences has a long history -- predating recognition of their legitimacy by science. Fundamental significance was notably attributed to them from a symbolist perspective. Curiously much of that language has been 'appropriated' in scientific use of the term as previously discussed (Theories of Correspondences -- and potential equivalences between them in correlative thinking, 2007).

The latter document highlights the related questions of the possible connectivity between topics arising from accepting a degree of validity to certain correspondences. This in turn raises the question of the credibility of that pattern of connectivity. Such issues are of considerable potential importance when tenuous patterns of connectivity are held to be viable carriers of meaning -- and a key to comprehension. This is most evident in the arts with respect to 're-cognition' of beauty. It is important in the case of myth, given the latter's traditional role and its modern variants as previously discussed (Relevance of Mythopoeic Insights to Global Challenges: cognitive integration implied by the Lord of the Rings, 2009).

Such patterns are most obviously 'moving' in poetry, music and song characterized as they are by a degree of memorable resonance between associations. These may be far more powerful than any logical connections between topics in different threaded discourses. Hence the argument for exploring the relevance to governance (A Singable Earth Charter, EU Constitution or Global Ethic? 2006).

Presumably psychoactive engagement with such vibrant patterns is a feature of the moving power of any magic carpet and the coherence it offers. The suggestive power of resonance is evident in the acoustics of the design of temples, notably mosques. The metaphor is important in Hinduism (Joachim-Ernst Berendt, The World Is Sound: Nada Brahma: music and the landscape of consciousness, 1983; The Third Ear: on listening to the world, 1992). Its significance is evident in the use of 'vibration' ('vibes') as a common descriptor of an attractive pattern of discourse -- and the sense in which any thread is held to be 'alive'.

How then are higher degrees of correspondence, connectivity and resonance to be embedded in the design of any such carpet -- given that it is the 'life' of a carpet that is the focus of Alexander's research? How then to transcend the collective tendency to 'clomp around' a space of lower dimensionality -- notably the binary 'Us and Them' of conventional strategy (Us and Them: relating to challenging others, 2009)? Is transforming 'them' into 'us' the only route to epiphany -- as a COIN-style approach to 'hearts-and-minds', and full-spectrum dominance, would appear to imply?

Mystical significance of carpets

The symbolism of carpets (noted in the main paper) is associated with mystical significance in certain cases -- notably in carpets of the quality explored by Alexander. In his insightful review of Alexander's study of carpets, Seamon notes that:

He surmises that the weavers of most of these carpets were probably Sufis -- Islamic holy men and women who sought to encounter God through mystical rapture. The carpets were woven as one means to 'reach union with God' (p. 21). Each carpet tries to express 'the ultimate oneness of everything' and 'a pattern which is the infinite domain' (p. 21).

According to Seamon, Alexander began his study of the carpets, sensing they could teach him much about one of his major research and design interests -- wholeness and genuine order:

I began to realize that carpets had an immense lesson to teach me: that as organized examples of wholeness or oneness in space, they reach levels which are only very rarely reached in buildings. I realized, in short, that the makers of carpets knew something which, if I could master it, would teach me an enormous amount about my own art (p. 15).

It should be noted that the controversy associated with Alexander's approach to carpets notably focuses on his highlighting their 'mystical' significance in contrast to more conventional analyses -- as in the otherwise valuable illustrated review by Detlev Fischer (Alexander's theory 'A foreshadowing of 21st century art - The color and geometry of very early Turkish carpets', 2009).

The narrative begins when the Angel Gabriel places the Prophet on a magic carpet. The magic carpet then floats him into the awesome and dazzling presence of Allah -- a presence that Muhammed... describes as 'a thing too stupendous for the tongue to tell of or the imagination to picture'. (p. 141)

Irrespective of the mystical significance attached to certain patterns and symbols within Islam, it should not be forgotten that equivalent symbols are to be found in Hinduism and Buddhism to which such significance is also attached. The obvious examples in each case are the yantra and the mandala in its many forms (Giuseppe Tucci, The Theory and Practice of the Mandala, 1973). Both figure in carpet designs -- more commonly used as wall hangings. Equivalents are to be found in Christianity (Painton Cowen, The Rose Window, 2005) and occultism (Owen Davies, Grimoires: a history of magic books, 2009). The construction of any such psychoactive device may be an important focus for certain schools of psychotherapy and for certain spiritual disciplines and practices of meditation.

The cognitive question is the nature of the mystery associated with the spiritual significance attached by some to carpets of quality. Alexander makes every effort to discover how they become powerful and alive. This is presumably intrinsic to any mystical experience -- effectively through their becoming 'enspirited' as a psychoactive attractor. More has been made of this with respect to the use of mandalas and yantras in meditation -- in controlling the movement and focus of attention. Ironically clues to the quest for such 'movement' through the noosphere may possibly be found in more accessible understandings of physical movement (Navigating Alternative Conceptual Realities: clues to the dynamics of enacting new paradigms through movement, 2002).

'Prayer mat' as 'System diagram' ?

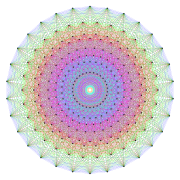

Representing higher dimensional complexity: Given these arguments, it is intriguing to speculate from a mathematical perspective on the relation between the cognitive framework of a carpet and that of 'a thing too stupendous for the tongue to tell of or the imagination to picture'. A carpet is readily understood as a 2-dimensional framework. If the observer's perspective is fundamentally identified with that 2-dimensional framework, and then successively exposed to 3, 4, 5...N dimensions, these can only be registered within that 2-dimensional framework as increasingly complex patterned projections.

In this sense it is of interest to note the attempt by mathematicians to represent, to the extent possible, the 'objects' of extremely high orders of symmetry only recently discovered. To the extent that they can be portrayed through distorting projections, their patterns are highly reminiscent of those traditionally featured in Islamic design.

| Representation of Lie group |

|

It is appropriate to note that, such is the complexity of these patterns of higher dimensionality (as with the Lie group above), that the most complex is caricatured as the Monster Group (Mark Ronan, Symmetry and the Monster: one of the greatest quests of mathematics, 2006). Examples include the Gosset 421 polytope (an "8-dimensional semiregular uniform polytope composed of 17,280 7-simplex and 2,160 7-orthoplex facets") and the Fischer-Griess Monster (a group of finite order, "a giant snowflake in 196,884 dimensions composed of more elements than there are supposedly to be elementary particles in the universe, namely approximately 8 x 1053"). Known as the "Monster", for mathematicians it might ironically be considered the essence of "Beauty".

Symmetry fundamental to universal organization: The significance of the Monster is briefly well-summarized by Marcus du Sautoy (Finding Moonshine, 2007; Patterns that Hold Secrets to the Universe). The clues to its existence gave rise to a mathematical literature on "monstrous moonshine". It is certainly monstrous in the challenge it constitutes to comprehension. The challenge of its comprehension (by ordinary mortals) has been discussed separately (Dynamics of Symmetry Group Theorizing: comprehension of psycho-social implication, 2008).

Appropriately such symmetry is considered fundamental to the organization of the universe from a physical perspective -- as with Alexander's study of The Nature of Order (2003-4). Little effort has however been devoted to determining the relevance of such symmetry to the challenges of psychosocial organization of a global society in crisis as discussed elsewhere (Potential Psychosocial Significance of Monstrous Moonshine: an exceptional form of symmetry as a Rosetta stone for cognitive frameworks, 2007).

Mapping global systems: Any depiction of a highly articulated system in diagrammatic form is typically indigestible other than to specialists, notably cyberneticians. Such was the case with the first attempts to represent the system of world dynamics as in the widely publicized report to the Club of Rome (Donella H. Meadows, et al., The Limits to Growth, 1972). There is of course almost no requirement that such diagrams reflect any degree of elegance in their design, other than that minimally necessary to facilitate comprehension by those with whom such specialists may need to communicate.

The map for the US Joint Chiefs of Staff is necessarily not an exercise in elegance -- even if it is only the 'hearts and minds' of the generals which have to be engaged to motivate them in their undertaking. How is who expected to be 'moved' by such diagrammatic representations -- even if they recognize psychodynamics in some form (World Dynamics and Psychodynamics: a step towards making abstract 'world system' dynamic limitations meaningful to the individual, 1971) ?

Magic squares: In seeking clues on how to weave together the threads of meaning that might be supposed to be essential to a magic carpet, one valuable source is the organization of the array of metaphorically-described conditions of transformative change indicated by the I Ching and the Tao Te Ching as being relevant to change and decision-making.

Traditionally important in such representation is the mathematics of the magic square (9-fold Higher Order Patterning of Tao Te Ching Insights: possibilities in the mathematics of magic squares, cubes and hypercubes, 2003; Hyperspace Clues to the Psychology of the Pattern that Connects in the light of the 81 Tao Te Ching insights, 2003). The resulting pattern might well be understood as forming a magic carpet -- did one but know how to ride it.

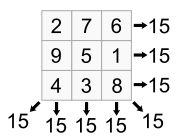

If any underlying systemic pattern is to be found in Alexander's 15 transformations, a mathematical curiosity of possible relevance is that all the dimensions of the smallest non-trivial magic square total to 15

|

To the extent that this is indeed of any relevance, the current strategic challenge of the 'nine planetary boundaries' and corresponding 'lifestyle diseases' has been specifically explored elsewhere (Cognitive Implications of Lifestyle Diseases of Rich and Poor: transforming personal entanglement with the natural environment, 2010).

Prayer mat: In contrast to conventional system diagrams, designed to be 'looked at' by specialists, a prayer mat is designed for daily use by ordinary people who 'kneel on it' during prayer. Given the universal symbolism embodied in such designs (described in the main paper), users might well be understood as praying on a more sophisticated system diagram -- if not a representation of the most comprehensive, universal systems diagram. Any such representation could be understood as necessarily compressed, collapsed or conflated. The argument in the main paper is that such patterned interweaving potentially reflects that of the threaded discourse of requisite variety for sustainable development and navigation of the adaptive cycle -- potentially implicit in the Good Regulator theorem of cybernetics.

The design of a prayer mat, echoing the archetypal rnagic carpet, is distinguished by additional cognitive, psychoactive and mnemonic characteristics. It is an object widely admired for its beauty. As a genuine exercise in 'hearts and minds', it is effectively designed to enable and facilitate learning and engagement at many levels. It is indeed designed to 'move'.

By contrast the strategic map of the moment (as depicted above) is inherently 'ugly' as a carpet -- typically going nowhere new in the noosphere. Ironically there is every possibility that the Chiefs of Staff, supposedly to be empowered by it (coming as they do from a Judeo-Christian tradition), may collectively pray that it will 'work' -- knowing full well that if it fails they will be 'on the carpet'.

Curiously although the movement of a magic carpet may be of limited significance within the Christian tradition, that tradition cultivates anecdotal accounts of saints being physically levitated. More relevant however is the active Christian expectation of being 'raised up' -- whatever than can be comprehended to mean (Varieties of Rebirth: distinguishing ways of being 'born again', 2004). In a period of increasing faith-based governance, it would be a mistake to neglect whatever this understanding may imply (Future Challenge of Faith-based Governance, 2003). By the same token it is appropriate to recognize that for the elite Freemasonry membership, great importance is attached to the Master's Carpet (or the Master Mason's Chart) as the basic emblematical chart for instruction in that art -- a learning pathway (John Sherer, The Masonic Ladder, or the Nine Steps to Ancient Freemasonry, 1874).

With respect to faith-based governance, it is appropriate to note that the largest 'prayer mat' in the world is that at the Sheikh Zayed Mosque in Abu Dhabi (5,627 m2 with 2,268,000,000 knots) -- designed for simultaneous use by 9,000 people.

Levitating 'recursively' into higher dimensionality?

Projection of significance into a two-dimensionl framework: A magic carpet, as a 2-D frame of reference, may usefully be understood as a kind of cognitive 'elevator' platform through which intimations of higher dimensionality are successively obtained and explored. The designs on the carpet might then be understood as visual traces of the patterns of connectivity encountered in spaces of higher cognitive dimensionality -- projections of the cognitive experience of coherence into their symmetry. The carpet is then to be understood as 'imprinted' with the patterns encountered in any levitation process. It is both a record of the journey and a mnemonically organized 'driving manual'. This is perhaps more explicitly recognized with respect to mandalas and yantras.

The most insightful articulation of the constraints and assumptions associated with representation of meaning in text on a 2-D surface is provided by Michael Schiltz (Form and Medium: a mathematical reconstruction. Image and Narrative, August 2003). He explores the implication of the reader/writer and the relative value of representation on a torus, as discussed elsewhere (Comprehension of Requisite Variety for Sustainable Psychosocial Dynamics: transforming a matrix classification onto intertwined tori, 2006).

As seemingly implied by the study of Joël de Rosnay (The Macroscope: a new world scientific system, 1979), a magic carpet is a means of cognitively seeing systemically on a larger scale -- rather than in the physical sense implied by the zoom-out facility offered by Google Earth. Through the complexity (partially) comprehended, encompassed and embodied -- if not engendered -- it offers access to a form of Rosetta stone through which correspondences and connectivity between disparate discourses and threads of meaning can be 're-cognized'. Such access to 'global' discourse is distinct from that implied by the connectivity of social networking or by the translation facilities of Google (Future Generation through Global Conversation: in quest of collective well-being through conversation in the present moment, 1997).

There is an irony to the much-appreciated effort to explain 'globalization' as an Earth-flattening process -- presumably into two dimensions (Thomas L. Friedman, The World Is Flat, 2005). This might perhaps be understood as designing a carpet unfit for the purpose of moving in the noosphere -- of moving 'hearts and minds' (Irresponsible Dependence on a Flat Earth Mentality -- in response to global governance challenges, 2008). It is also indicative of the possibility of a cognitive 'down elevator' to lower dimensionality -- 'dumbing down'. Again it might be said that, aside from the threat of being 'on the carpet' (mentioned above), the only relevance of 'carpet' in the world of global strategy development is that of carpet bombing -- perhaps in the form of cultural violence. This might then be be characterized as 'cultural carpet bombing' -- as efforts to 'spread of democracy' and to deliver aid may be experienced by some cultures. More radically, Pakistan was recently threatened with being "bombed back to the Stone Age" -- physically or culturally?

Complex plane as a meaningful carpet: Relevant clues to the cognitive nature of any 'recursive levitation' are potentially to be found in another object of interest to mathematicians, namely the Mandelbrot set and its representation in the complex plane. Its discovery attracted widespread interest because of the inherent beauty of its visual rendering and the capacity to zoom into its fractal organization, as offered by many accessible applications (see extensive set of images at Visual Guide To Patterns In The Mandelbrot Set). Although at first sight simple to the eye, its deep structure eludes simple definition because of the manner in which it embodies complexity coherently. The question is the nature of the insights it offers into psychosocial complexity (Psycho-social Significance of the Mandelbrot Set: a sustainable boundary between chaos and order. 2005).

The detail accessible through any visual rendering of the Mandelbrot set offers patterns with an intriguing degree of resemblance to those of many traditional carpet designs. The fractal nature of some carpet patterns has been noted above (see Mamta Rani and Vinod Kumar, New Fractal Carpets, Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 29, 2004, 2C; Mamta Rani and Saurabh Goel, Categorization of new fractal carpets, Chaos, Solitons and Fractals, 41, 2, July 2009). The rendering of the Mandelbrot set could well be the basis for the weaving of an elegant carpet design. This could provide an interesting case for exploration of Alexander's 15 transformations.

There is also a charming sense in which one visual rendering of the Mandelbrot set, of different orientation, has been labelled the Buddhabrot, given its resemblance to a seated figure. To the extent that the figure on the carpet is most appropriately represented geometrically as a cognitive complex -- interfacing with higher dimensionality through movement of the carpet -- it is understandable that conventional depictions of Muhammed are prohibited as inappropriate by Islam.

Self-reflexive cognitive engagement: Whilst laudable, The Macroscope avoids the cognitive dimension of the nature of the engagement with what is visually 'scoped'. In so doing it follows the emphases over recent decades of the systems and cybernetics disciplines, obscuring the inspiration of earlier 'general systems research' and the cognitive emphases promoted by such as Erich Jantsch (The Self-Organizing Universe: scientific and human implications of the emerging paradigm of evolution, 1980) or V. V. Nalimov (Realms of the Unconscious: the enchanted frontier, 1982). Such approaches are essentially non-self-reflexive in contrast to the sense which appears to be increasingly vital (Consciously Self-reflexive Global Initiatives: Renaissance zones, complex adaptive systems, and third order organizations, 2007).

Potentially more intriguing in the cognitive process of 'recursive levitation' is the increasing degree of reflexivity. Self is increasingly reflected in Other, and vice versa, as suggested by such as Henryk Skolimowski (The Participatory Mind: a new theory of knowledge and of the universe, 1995), Douglas Hofstadter (I Am a Strange Loop, 2007; Gödel, Escher, Bach, 1979) and Gregory Bateson (Mind and Nature: a necessary unity, 1979).

The structure of the seated figure is mirrored by that of the carpet as a constrained projection of the experience of the process. In this respect the concordance between the implications of the fractal order of nature, as articulated by Benoit Mandelbrot (The Fractal Geometry of Nature, 1982) and Alexander (The Nature of Order, 2003-4), stress the principle of self-similarity. It is the manner of this cognitive engagement with beauty that would seem partially, but significantly, to elude the focus of Alexander -- despite the relevance to healing. This is the resemblance to the whole of the part (the seated figure) -- implying a degree of symmetry -- a point significantly argued with respect to cultural artefacts (Aaron Haspel, The Fractal Geometry of a Poem, God of the Machine, 2006). The challenge is how the fractal organization of the Mandelbrot set is 'reconciled' with that of increasingly complex symmetry groups and 'rendered' into a comprehensible carpet design.

The 'levitation' might be understood in terms of traversing a toroidal form in a cognitive hyperspace -- only to meet oneself, as intimated by poets and mystics. Relevant arguments have been presented elsewhere (Stepping into, or through, the Mirror: embodying alternative scenario patterns, 2008; Self-reflective Embodiment of Transdisciplinary Integration (SETI) the universal criterion of species maturity? 2008; Psychosocial Energy from Polarization within a Cyclic Pattern of Enantiodromia, 2007; Hyperaction through Hypercomprehension and Hyperdrive -- necessary complement to proliferation of hypermedia in hypersociety, 2006). The toroidal organization of cognition appropriate to any such movement has long been symbolized by the Ourobouros -- the snake or dragon 'biting its tail'.

Curiously in the quest for nuclear fusion power, a toroidal form (tokamak) has proven to be necessary for the appropriate management of plasma -- whose dynamics are described in the technical literature in terms of snake metaphors. Cognitive parallels can be fruitfully explored (Enactivating a Cognitive Fusion Reactor: Imaginal Transformation of Energy Resourcing (ITER-8), 2006). A complementary case can also be made regarding the vigilance required with any such psychoactive technology (Overpopulation Debate as a Psychosocial Hazard, 2009; Psychoactive Text Warning: enneagram of precautionary attitudes, 2007).

Any Rosetta stone enables access to the 'pattern that connects' (Enactivating "the pattern that connects, 2006) as indicated by Gregory Bateson (1979) in making the point that:

The pattern which connects is a meta-pattern. It is a pattern of patterns. It is that meta-pattern which defines the vast generalization that, indeed, it is patterns which connect.

And it is from this perspective that he warns in a much-cited phrase: "Break the pattern which connects the items of learning and you necessarily destroy all quality."

Transcendence of naming and description: There is an extremely unfortunate tendency to name cultural artefacts possessively, whether it be scientific discoveries (like the 'Mandelbrot set'), theories, belief systems, or even probably the 'Alexander transformations' -- as well as any Theory of Everything (Musing on Information of a Higher Quality, 1996). This is an extension of the desire to possess beauty exclusively (mentioned above). There is every possibility that this denatures the most fundamental cognitive experiences -- constituting an indicator of failure to 're-cognize' them -- as argued with respect to apophasis (Being What You Want: problematic kataphatic identity vs. potential of apophatic identity? 2008). The briefest articulation of this inadequacy is the first verse of the Tao Te Ching:

The Way that can be described is not the absolute Way;

the name that can be given is not the absolute name.

Nameless it is the source of heaven and earth;

named it is the mother of all things.

This problem applies notably to the figure 'on' any magic carpet. Arguably the carpet will only 'fly' -- bearing identity cognitively into higher dimensions -- if possessive naming and identification is also transcended. This suggests fruitful reflection on the cognitive implication of 'recursive levitation'.

In a sense the 'Mandelbrot set' is a presentation of a relationship between the geometric simplicity of the central (seated) figure and the complexity of surrounding infinity -- and of the complex boundary between them. To the extent that the former is suggestive of the individual's cognitive capacity and the latter is suggestive of the universe (and the complexity associated with deity), the rendering offers a remarkable visual metaphor of the relationship between 'self' and 'other'. As noted above, the symbolism of many carpets seeks to echo this relationship with the universe in its cognitive and existential implications.

Quest for mnemonic catalysts: the beauty of a magic carpet

Representations of the global crisis of crises using the rich array of computer-aided visualization do not as yet seem to engage, engender and motivate to enable new modes of comprehension and action. The qualities built into the design of a carpet, of the kind analyzed by Alexander, suggest the possibility of psychoactive devices for encompassing these challenges, as envisaged previously (In Quest of Mnemonic Catalysts -- for comprehension of complex psychosocial dynamics, 2007; Imagining the Real Challenge and Realizing the Imaginal Pathway of Sustainable Transformation, 2007).

Clearly attention could be fruitfully focused on why system diagrams and other devices are essentially unattractive and unengaging. They do not echo -- or seek to echo -- the sense of wholeness which is associated with the carpet weaves to which reference has been made. And yet the mathematical insights into the highest orders of symmetry of greatest 'beauty' -- patterns echoed in the design of such carpet weaves -- are dissociated from the 'ugly' representations of global dynamics currently promoted as triggers for collective global action.

How is 'magic' to be woven into any such representation such as to engage 'hearts and minds'?

| Power/Engagement vs Conceptual articulation (perhaps to be understood as a reconciliation between 'topsight' and insight') |

|

In concluding his summary of Nature and Order, Alexander's (New Concepts in Complexity Theory -- arising from studies in the field of architecture, 2003) affirms:

The beauty of naturally occurring patterns and forms has rarely been discussed as a practical matter, as something needing to be explained, and as part of science itself. Yet the fifteen transformations, if indeed they provide a primary thrust in the engine of evolution, give us a way of understanding how beauty -- aesthetics -- plays a concrete role, not an incidental role, in the formation of the universe.

Although he explicitly addresses the role of cognition in the appreciation of beauty, an understanding of the psychoactive engagement with beauty and how it is engendered could well have been integrated into such a conclusion. Alexander continues with a plea for a more beautiful science:

...one which really deals with the world, one which not only helps us to understand, but which also goes to a deeper level, and begins to encompass the wisdom of the artist, and beings to take its responsibility in healing the world which unintentionally it has so far created, and which it has, sadly, and unintentionally, so far helped to destroy.

In such a world, scientists would do better, the profound questions of health, wholeness, nature, ecology, and human joy would be part of a single world view, in which it would be recognized as part of science -- scientia -- that is to say, knowledge -- and in which scientists and artists together, speaking a common language, would take part in this joy, to the benefit of all mankind....

Of course there are some who would say that work of this kind is wholly inappropriate for science, and that they prefer a vision of science which is more modest in scale, and deals mainly with potentially and immediately answerable questions.

Crudely put, might the interweaving of the threads of meaning in the threaded discourses of mainstream science (as currently practiced) be described as (worn) 'threadbare' in comparison with the strategic challenge of weaving a magic carpet? A strong case can be made for exploring Alexander's approach in relation to lifestyle diseases, as discussed previously (Cognitive Implications of Lifestyle Diseases of Rich and Poor: transforming personal entanglement with the natural environment, 2010).

[NB: A follow-up to the above arguments, with a detailed review of Christopher Alexander' insights, is provided in a separate paper: Harmony-Comprehension and Wholeness-Engendering: eliciting psychosocial transformational principles from design (2010)].

References

Christopher Alexander:

- Notes on the Synthesis of Form. 1964 [summary]

- A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press, 1977 [summary]

- The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press, 1979 [summary]

- A Foreshadowing of 21st Century Art: the color and geometry of very early Turkish carpets. Oxford University Press, 1993 [review]

- The Nature of Order: an essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe. Center for Environmental Structure, 2003-4. [summary]

- New Concepts in Complexity Theory: an overview of the four books of the Nature of Order with emphasis on the scientific problems which are raised. 2003 [text]

- Harmony-Seeking Computations: a science of non-classical dynamics based on the progressive evolution of the larger whole. International Journal for Unconventional Computing (IJUC), 5, 2009 [text]

Ron Atkin:

- Multidimensional Man; can man live in 3-dimensional space? Penguin , 1981 [summary]

- Combinatorial Connectivities in Social Systems. Birkhäuser Verlag, 1977

Gregory Bateson. Mind and Nature; a necessary unity. New York, Dutton, 1979

Joachim-Ernst Berendt:

- The World Is Sound: Nada Brahma: music and the landscape of consciousness. Inner Traditions, 1983

- The Third Ear: on listening to the world. Henry Holt, 1992

Carol Bier:

- Symmetry and Pattern: The Art of Oriental Carpets, 1997, a collaborative project of The Textile Museum and The Math Forum. [text]

- Mathematical Truth and Beauty: The Case of Oriental Carpets, Institute for the Humanities Notes (University of Michigan), 1998

- Symmetry and Symmetry-Breaking in Oriental Carpets, ISIS-Symmetry, 2000

- Choices and Constraints: Pattern Formation in Oriental Carpets, Forma (Journal of the Society for Science on Form, Japan) 15, no.2, pp. 127-132 [text]

- Mathematical Aspects of Oriental Carpets, 2001 [text]

Scott A. Boorman. A Protracted Game: a wei-ch'i interpretation of maoist revolutionary strategy. Oxford University Press, 1969 [summary]

Eric Broug. Islamic Geometric Patterns. Thames and Hudson, 2008

Stuart Cowan. The Nature of Order: unfolding a sustainable world. Resurgence, 2004 [text]

Keith Critchlow. Islamic Patterns: an analytical and cosmological approach. Inner Traditions,1976

Joël de Rosnay. The Macroscope: a new world scientific system. Harper and Row, 1979 [extracts]